Desde el Colegio recomendamos la publicación de Carolina Plaza Colodro en Political Observer on Populism (POP)

“The spanish party system is mutating: a journey through multiple crises”

Carolina Plaza Colodro describes the mutations that characterized the Spanish party system during the last decade. Corruption scandals, the management of austerity, and the reactivation of regional identities are among the factors that brought to the end of a bipartisan system based on the centre-right PP and the centre-left PSOE. Populism found favourable opportunity structures and emerged from the necessity of democratic regeneration, marked by a triple crisis: economic, political, and territorial. Podemos, once in power, started struggling to maintain its anti-establishment rhetoric, while the growing role of VOX ended the so-called Spanish exceptionalism, introducing yet another mutation in the Spanish party system, with important implication for the country’s democracy.

Enjoy the read.

The Spanish party system has greatly changed over the last decade especially due to a rising polarised political climate marked by instability, little harmony between territorial authorities and a high level of distrust among citizens towards politicians. In less than ten years, the Spanish party system went from bipartisan to multi-partisan. Since the first post-crisis elections in 2015, the two majority parties the People’s Party (Partido Popular, PP) and the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) suffered a significant decline, reaching together only 50% of the vote (compared to 73.39 in 2011 and 83.81 in 2008) while new political parties occupy the electoral space. Highly fragmented results, together with a high level of government-opposition polarization and the inability of the political parties to form coalition governments, led to a very unstable political climate in which there have been votes of no confidence, electoral surprises, and multiple elections.

The two traditional cleavages that structure the political competition in Spain are the left-right and the centre-periphery. The depth of the crisis of representation and party system change in Spain is intimately linked to the decline of bipartisanship, the emergence of new political parties and the activation of populism on the political scene, all these triggered by a deep change in the public debate. Both mainstream parties were severely punished in polls, mainly due to corruption scandals and public perceptions of the alleged joint responsibility in the mismanagement of the economy and their inability to alleviate the worst consequences of austerity. In addition, in the last decade, as a result of Catalonia’s demands for independence, took place an exacerbation of the centre-periphery cleavage and issues related to the nation and the territorial model. As a result, national and regional identities started to dominate the public debate. New parties positioned themselves in the political scene denouncing political corruption and articulating a discourse focused on democratic regeneration.

Kang and Kodos, pretending to be Bob Dole and Bill Clinton in 1996: since no one is willing to vote for a third party, Kang wins.

Kang and Kodos, pretending to be Bob Dole and Bill Clinton in 1996: since no one is willing to vote for a third party, Kang wins.

In a context of high economic pressure and strong political crisis in which citizens feel a profound disenchantment with established politics, populism is one of the main driving forces of the realignment process. However, it is essential to distinguish two processes that run in parallel and were able to open the political space for populist demands of different nature. First, the Great Recession and the subsequent implementation of austerity policies, that foster economic debates and benefited the populist radical left. The emergence of Podemos drives the first transformation of the Spanish party system, channelling the discontent arising from the economic crisis. Second, the territorial crisis activated by the independence demands of the parties conforming the Catalan government that trigger cultural and identitarian debates and nurtured the populist radical right. In 2019 the Spanish party system changed again when VOX enters parliament and puts an end to the Spanish exceptionalism, consisting in the failure of radical right parties that characterised the country since the end of Franco’s regime.

In Spain, the electoral effects of the Great Recession were not visible until 2011. In 2010, the government of the PSOE led by Rodríguez Zapatero, implemented the first austerity package, which unleashed a wave of social mobilization, the 15M or Indignados Movement. This social movement verbalized the incipient representation crisis claiming that the mainstream parties, PP and PSOE, were alike and their programmatic profiles and policies proposals undistinguishable. In 2011, at the peak of the social unrest, new elections were held and the main opposition party, the PP, won with an absolute majority. The PP continued the implementation of austerity measures, which, together with the multiple corruption scandals that were uncovered in the first months of the legislature, considerably eroded public support for the party. In sum, in Spain bipartisanship deepest decline was linked to the participation of first the PSOE and then the PP in the implementation of austerity measures, besides reaching other political agreements, and their involvement in corruption scandals. All of this contributed to the perception promoted by the 15M that mainstream political parties were alike (despite their different ideologies, being in office or in opposition).

The 2014 European elections turned out to be crucial in the transformation of the Spanish party system. The crisis of the two mainstream parties opened the political opportunity structure and allowed the emergence of new parties. Ciudadanos: party born in 2006, with a discourse focused on democratic regeneration and the tensions in the center-periphery axis that were unleashed around the separatist intentions of Catalonia. Podemos: a populist party that emphasized issues related to redistribution and that voiced a critical position against austerity. It is the emergence of Podemos that drives the first transformation of the Spanish party system, channelling the discontent arising from the economic crisis. Podemos was founded in 2014 as a result of the 15-M protests against austerity and political corruption, taking a left position against austerity and a libertarian stance on social issues and framing these positions as part of a struggle of the people (la gente) against the caste.

Podemos’ entry into the Spanish party system did not bring a strictly ideological transformation, given the similarities with United Left (Izquierda Unida, IU), the traditional Spanish radical left party, but rather political, because Podemos has explicitly proposed a prototype of radical left populism. Podemos unequivocally make the “honest people” and the “corrupt elite” the central and most relevant division in its interpretation of Spanish politics. The attacks of Podemos against the ‘caste’ were numerous in 2014, when the party was moving its first steps. Later on, Podemos moderated such statements and nuanced its proposals with more classical left-wing references (e.g. declaring that Podemos’ policies represented ‘real social democracy’). The leaders of Podemos have never hidden their populist inspiration (modulated with nationalist or, in their own words, “patriotic” civic pretensions), while in its early days (and before forming an electoral alliance with IU) the party avoided declaring itself to be on the left and declared that the left-right division was already irrelevant in Spanish politics.

On the other hand, in Spain electoral competition is also articulated around the center-periphery axis, which in recent years has strongly polarized the Spanish political space. Tensions around Catalonia’s demands for independence have facilitated the emergence of VOX, a right-wing populist party which has mobilized nationalist issues in the Spanish electoral arenas. VOX was created in 2013 by former members of the PP, Spain’s main conservative party, who were unhappy with what they perceived as a tendency towards moderation on issues such as economic liberalism, traditional values and the unity of Spain. Between 2014 and 2016, VOX participated in different elections, obtaining insignificant voting percentages that left it out of the representation chambers. However, it made its institutional entry into the Andalusian elections of 2018, with 12 seats that allowed VOX to support a change of government in the region. In the general elections held on April 2019, VOX got around 2,000,000 votes and 24 seats, finally entering the Spanish Congress of Deputies, which increased substantially in the elections held again in November 2019 (3.6 million votes, approximately 15% of the valid votes). For the first time in Spain’s recent democratic history, a radical right-wing party obtained representation in parliament (52 seats out of 350), putting an end to the “Spanish exception”.

Thus, in 2019 the Spanish party system suffered its second transformation. From its foundation, VOX embraced a discourse characterised by a combination of authoritarianism, nativism, nationalism, and economic liberalism. Unlike other contemporary radical right-wing parties, the anti-immigration discourse is not at the very heart of their electoral platform, which focuses mainly on the national question and the challenges posed by the state of autonomies and, more recently, secessionism. In other words, VOX, more than defending national sovereignty against the intervention of supranational powers, has mobilized national identity against political options that, according to their imaginary, threaten the sovereignty of the country from within. Unlike other parties in this family, the articulation of a populist discourse is not a central part of its political stance.

In the current crisis arising from the coronavirus pandemic, space opened up for populism but it is unclear what type of populism will thrive. This will depend on several elements, such as the government-opposition dynamics and the frameworks used to discuss the virus. The pandemic brought a change in the public debate, which now focuses more on economy (redistribution, taxes, public services) rather than on identity.

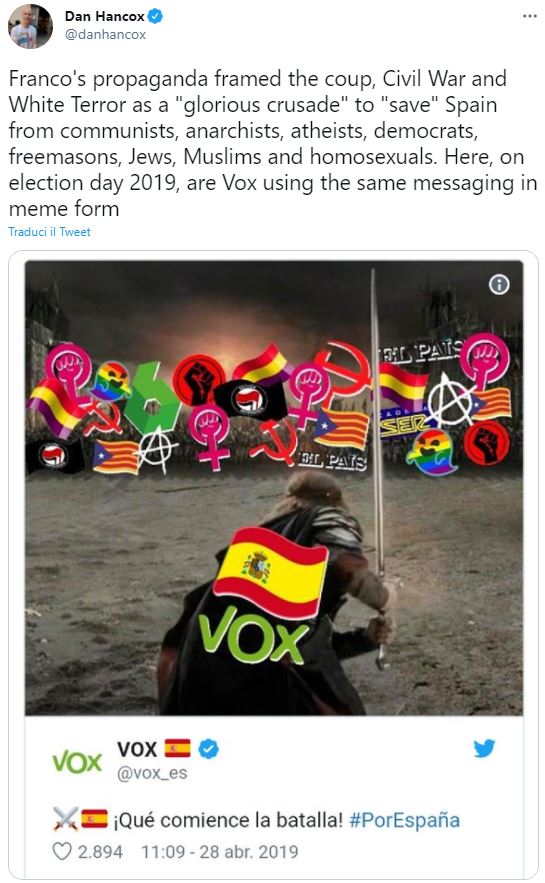

Podemos attacks Ciudadanos for criticizing corruption in 2016 and then accepting it in 2019. Excellent example of politics of memes.

Podemos attacks Ciudadanos for criticizing corruption in 2016 and then accepting it in 2019. Excellent example of politics of memes.

However, Podemos -being part of the coalition government- cannot present itself as a challenger party and this allows right-wing populist actors to channel the discontent because the populist attribution of blame is much more effective when populist actors are not in power. That is why Podemos finds it more challenging to connect its anti-establishment rhetoric against the government with economic arguments, and Vox deployed a populist strategy in line with the European populist right, emphasising issues such as immigration and Euroscepticism.

The last moves of Podemos’ leader, Pablo Iglesias, who left the national government to run in the regional elections in Madrid, might indicate an attempt to tone up the populist rhetoric of the party, given that being in power Podemos cannot present itself as a challenger party. The next regional elections in Madrid on May 4, the survival of the governing coalition and the next general elections scheduled for 2023 will be critical in determining whether the dynamics of change of the Spanish party system will continue or, on the contrary, subside.

Carolina Plaza Colodro (@PlazaColodro) is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Area of Political Science at the University of Salamanca, Spain. She has been visiting researcher at Università Degli Studi di Milano (2016), University of Leicester (2016) and Universidade Nova da Lisboa (2020). In her postdoctoral project, she approaches the intersection between populist attitudes, political preferences and socioeconomic characteristics of the different social groups and their role in party system transformation. Her investigations have been published in West European Politics, Electoral Studies and Politics, among others.

0 Comentarios

No hay comentarios aún

Puedes ser el primero para comentar esta entrada